Intro to the metal lathe: Difference between revisions

(add concentricity images) |

(Add concentricity and rigidity notes) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[:Category:Lathes -- Metal|Metal lathes]] are versatile tools that we use to make precise round parts. These kinds of precise round parts show up in everything from small consumer goods to heavy industrial machinery, and they make smooth and efficient movement possible. Metal lathes achieve this through accurate linear movement and rigidity, which allows us to make parts with exacting dimensions and concentric features. In this class, we'll learn how to safely operate the manual metal lathes, produce some simple parts, and explore some of the many ways we can fabricate parts with a manual metal lathe. | [[:Category:Lathes -- Metal|Metal lathes]] are versatile tools that we use to make precise round parts. These kinds of precise round parts show up in everything from small consumer goods to heavy industrial machinery, and they make smooth and efficient movement possible. Metal lathes achieve this through accurate linear movement and rigidity, which allows us to make parts with exacting dimensions and concentric features. In this class, we'll learn how to safely operate the manual metal lathes, produce some simple parts, and explore some of the many ways we can fabricate parts with a manual metal lathe. | ||

== How Does a Metal Lathe Work? == | |||

== | === Overview === | ||

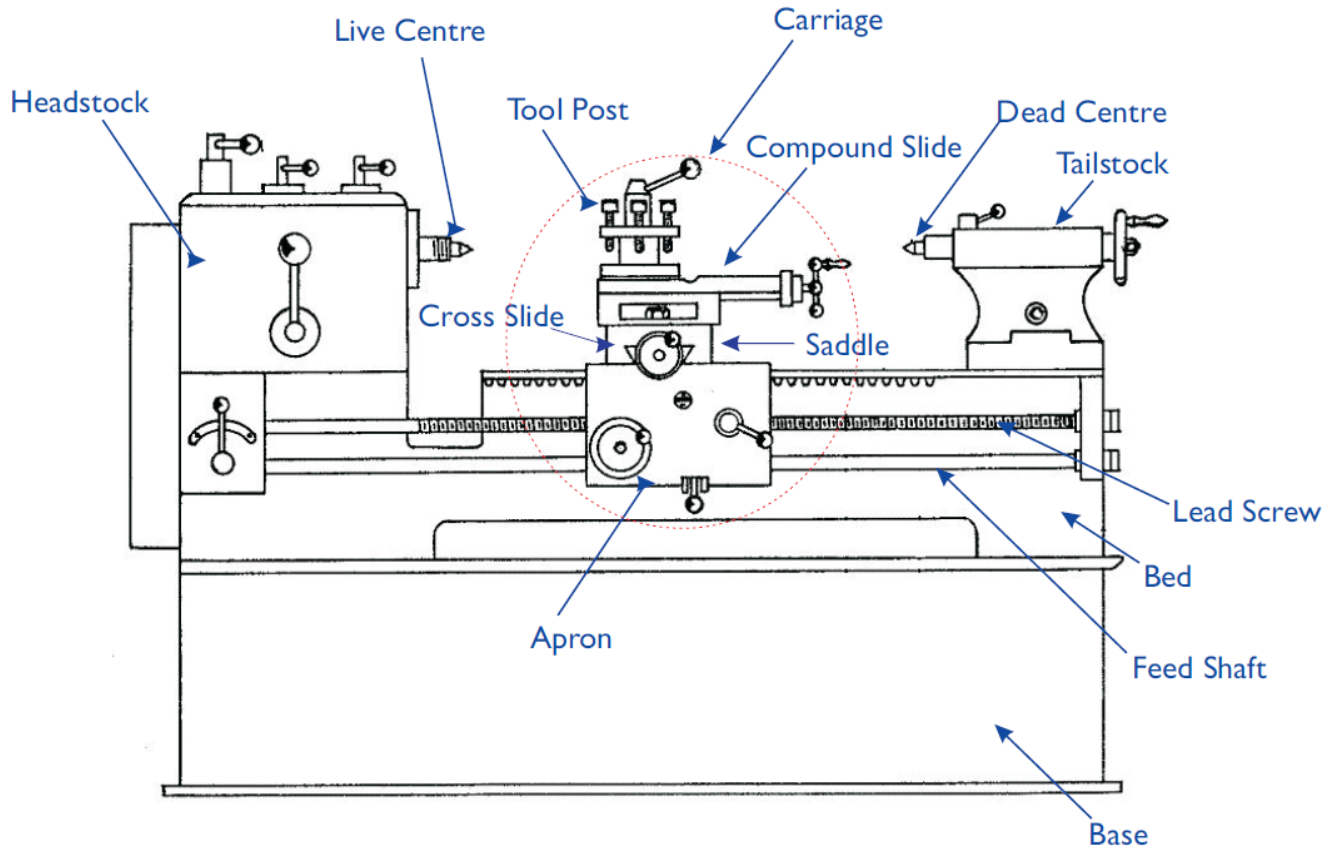

[[File:Parts of a lathe2 labeled.png|alt=Components of a metal lathe|thumb|Major components of a metal lathe. The lathe holds the work in a chuck affixed to the ''headstock'' or between centers (as shown above). The ''carriage'' moves the tool parallel to the spindle bore, the ''cross slide'' moves the tool perpendicular to the spindle bore, and the ''compound slide'' (sometimes called the ''top slide'') can move at an adjustable compound angle. Several controls for moving the carriage and slides are located on the ''apron''.]] | |||

The lathe holds material securely and spins it along the axis of the spindle bore. As the material spins, operators can move a cutting tool against the work parallel to the spindle bore with the ''carriage'', which travels along the ''ways'', the prismatic rails on the bed of the ways. Users can also move the tool perpendicular to the work with the ''cross slide'', and at a compound angle with the ''compound'' (often referred to as the ''top slide''). Users can adjust the depth of cut by adjusting these controls in unison, allowing them to make round, concentric features with precise dimensions. | |||

=== Concentricity: the | ==== Concentricity: the Superpower of a Metal Lathe ==== | ||

The spindle of the lathe spins in an accurate circle, so every cut will produce a feature concentric with the spindle axis. The lathe has precisely machined axes, so the carriage will move parallel to the spindle axis, and the cross slide will move perpendicular to the spindle axis. ''Turning'' cuts with the carriage will produce precise cylindrical features, while ''facing'' cuts with the cross slide will produce flat surfaces perpendicular to the spindle axis.<gallery> | |||

File:Concentric.png|The circles in this bullseye share the same center, so they're ''concentric''. | |||

File:Eccentric.png|The circles in this bullseye do not share the same centers, so they're ''eccentric''. | |||

</gallery> | |||

===== Rigidity: the Corollary to the Metal Lathe Superpower ===== | |||

The ways of the lathe are parallel to the spindle bore, and the cross slide movement is perpendicular to the spindle bore. Ideally, all cuts would follow these parallel and perpendicular constraints, but the intense cutting forces cause all of the components -- the work, the tools, and even the lathe itself -- to flex to some degree. We try to minimize this by building the lathe out of sturdy materials; [[South Bend Manual Lathe|the South Bend 9A]], the smallest lathe in the machine shop, weighs over a half a ton. We also reduce the amount of flex by limiting both tool and material stick-out and controlling the aggressiveness of our cuts. | |||

Revision as of 20:34, 2 April 2024

Metal lathes are versatile tools that we use to make precise round parts. These kinds of precise round parts show up in everything from small consumer goods to heavy industrial machinery, and they make smooth and efficient movement possible. Metal lathes achieve this through accurate linear movement and rigidity, which allows us to make parts with exacting dimensions and concentric features. In this class, we'll learn how to safely operate the manual metal lathes, produce some simple parts, and explore some of the many ways we can fabricate parts with a manual metal lathe.

How Does a Metal Lathe Work?

Overview

The lathe holds material securely and spins it along the axis of the spindle bore. As the material spins, operators can move a cutting tool against the work parallel to the spindle bore with the carriage, which travels along the ways, the prismatic rails on the bed of the ways. Users can also move the tool perpendicular to the work with the cross slide, and at a compound angle with the compound (often referred to as the top slide). Users can adjust the depth of cut by adjusting these controls in unison, allowing them to make round, concentric features with precise dimensions.

Concentricity: the Superpower of a Metal Lathe

The spindle of the lathe spins in an accurate circle, so every cut will produce a feature concentric with the spindle axis. The lathe has precisely machined axes, so the carriage will move parallel to the spindle axis, and the cross slide will move perpendicular to the spindle axis. Turning cuts with the carriage will produce precise cylindrical features, while facing cuts with the cross slide will produce flat surfaces perpendicular to the spindle axis.

Rigidity: the Corollary to the Metal Lathe Superpower

The ways of the lathe are parallel to the spindle bore, and the cross slide movement is perpendicular to the spindle bore. Ideally, all cuts would follow these parallel and perpendicular constraints, but the intense cutting forces cause all of the components -- the work, the tools, and even the lathe itself -- to flex to some degree. We try to minimize this by building the lathe out of sturdy materials; the South Bend 9A, the smallest lathe in the machine shop, weighs over a half a ton. We also reduce the amount of flex by limiting both tool and material stick-out and controlling the aggressiveness of our cuts.